My Estuary: Matt Gregg

Farming Oysters on the Jersey Shore

By Rob Shane

Coastal New Jersey is known to most as a booming vacation destination with pristine beaches and destination resorts. In the past decade, though, a movement to turn New Jersey’s largest body of water, Barnegat Bay, into an oyster farming destination has taken off.

The man at the forefront of this effort was Matt Gregg, founder of Forty North Oyster Farms and the Barnegat Oyster Collective. A native son of the Garden State, Matt got his first taste of work as a teenager in the fish markets along the Shark River and then as a mate on local fishing boats. This initial interest led him to pursue a degree in aquaculture, fisheries, and marine policy at the University of Rhode Island. Like most successful entrepreneurs, through his collective experience Matt recognized an opportunity and seized it.

Barnegat Bay lies entirely within Ocean County, NJ and supports a robust coastal economy flush with tourism, commercial and recreational fishing, and of course oyster farming. Most of these industries boom from May – September with the influx of vacationers and shut their doors as the colder months take hold.

Matt’s business doesn’t get a break, though, and as he likes to say, “we don’t lose our customers in the Fall, Winter and Spring, they just go to different places.” By selling direct to restaurants from New York to Philadelphia, operating a farm in Central Jersey puts him in a prime location to reach tens of millions of people in just a two-hour drive.

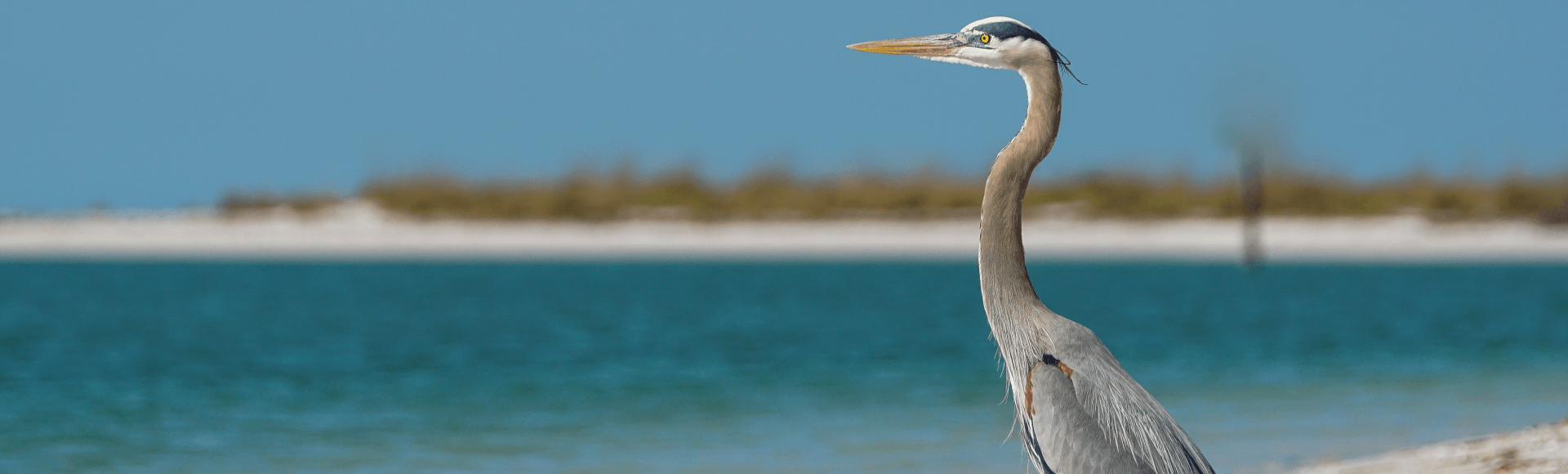

On a Monday afternoon in late October, I was fortunate enough to get a firsthand tour of Matt’s farm – a 12-acre plot of estuary just a few hundred yards from the iconic Barnegat Lighthouse. As we motored out of a small marina and came around the bend, the first thing I noticed were hundreds of pelicans perched atop a maze of ropes and cages holding the operation together. This may not seem too out of the ordinary, except that on a 360-degree observation not another pelican was to be seen anywhere in the entire bay. Sea urchins, seals, and striped bass also call his farm home.

yards from the iconic Barnegat Lighthouse. As we motored out of a small marina and came around the bend, the first thing I noticed were hundreds of pelicans perched atop a maze of ropes and cages holding the operation together. This may not seem too out of the ordinary, except that on a 360-degree observation not another pelican was to be seen anywhere in the entire bay. Sea urchins, seals, and striped bass also call his farm home.

It’s the kind of circulatory economy that makes operations like this so important to our estuaries. Matt’s oysters don’t just put food on his plate, figuratively and literally, they support secondary and tertiary businesses that have grown to depend on him as well. Recreational anglers have identified his farm as a hot spot to enjoy catching fish. Bird watchers pay for the opportunity to see these pelicans, which Matt tells me is not a common sight in New Jersey. Many of them rent boats and buy gas, ice, bait, and snacks at the same small marina we departed from.

At the end of the day, they all rely on one thing – a healthy Barnegat Bay that can support the industries consumer’s demand.

New Jersey is the most densely populated state in the U.S. It ranks 11th in population but 47th in total area, ahead of only Connecticut, Delaware, and Rhode Island. Home to more than 8 million people, that equates to about 1,200 people/sq. mile. This tracks with estuaries across America, which account for only 4% of U.S. land mass but are home to 40% of the country’s population.

If you’re in the business of selling oysters, that many people at your backdoor is a huge market opportunity. That level of density, though, is a constant strain on the state’s water resources. This puts Matt and his business are at the confluence of environmental consciousness and economic productivity. This density has come at a cost to the state’s natural infrastructure. Matt’s farm is lucky to be positioned just behind Island Beach State Park on one side; a largely untouched barrier island that maintains predevelopment ruggedness and no permanent settlement. New shopping centers, homes, and roads dot the landscape on the opposite side of Barnegat Inlet and have stripped most of the region of its natural defense, instead relying on stormwater management systems that may not be equipped to handle our current climate predicament.

Since Forty North Oysters produces a food product, they must also meet standards set forth by the Food and Drug Administration and state agencies. To farm shellfish in New Jersey’s estuaries, not only do you have to meet water quality standards, but there cannot be any existing populations of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), such as eelgrass, or any endangered species. Since passage of the Clean Water Act, and subsequent legislative protections, New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), who issues permits for shellfish farms, has been documenting water approved for shellfish harvesting along the coast and it has consistently increased due to improved water quality.

Matt and his oysters are now facing another threat in the form of global warming, though. Seas are rising and storms are becoming more regular and more intense. His ability to produce and sell locally-grown oysters depends on his ability to access the farm – which traditionally has sat in only a few feet of water. Even while on the phone with him during what he called a small nor’easter the entirety of his farm was flooded and kept him, and his crew, from working all day – an occurrence that’s becoming more and more frequent.

A horrifically ironic sign of the times are No-Wake signs that line the main street through the town of Surf City on Long Beach Island. Instructions meant for sea-faring vessels now beg cars and trucks to slow down during the regular flood events to avoid sending waves into people’s front yards or places of business. Stark evidence of climate change happening in real time.

Matt is hopeful that as more people flock to the coasts, we reconsider our approach to protecting our estuaries from the effects of climate change. In the updated Economic Value of America’s Estuaries report, RAE was able to estimate the value of natural infrastructure in Great Egg Harbor, just a few miles south of Matt’s farm, between $34 and $153 million. Of course, each estuary is different, and each natural ecosystem offers different benefits, but one can draw the correlation that the value is still significant.

Matt is also hopeful that his young son, should he choose to do so, will be able to take on the family business when he comes of age. Just about ten years into this voyage, he has seen the benefits of his farm translating to benefits in his local estuary. Wild oysters, a product of spawning oysters from local farms, are repopulating the Bay, providing habitat for fish and wildlife, filtering water, and protecting the shores from erosion. Seagrasses have started growing near his farm. Although he won’t take the credit outright, it’s hard to deny that the million plus oysters under his watch, and their ability to clean and filter water, have played some part in this.

At the end of our tour, Matt reached down into the unusually-warm-for-October water and pulled out a dozen fresh oysters for me to take home. As I enjoyed them a few days later around a campfire on Assateague National Seashore with friends, I couldn’t help but wonder what life without oyster farms in Barnegat Bay looks like. How close are we to that day? What does it mean for the restaurant owner? The fishing guide? The cashier at the marina? The estuary?

Check out the Barnegat Bay Collective to

find Forty North Oysters in a restaurant

near you. Special thanks to Matt Gregg

for showing me around and the

American Littoral Society for introducing

us. Read the full Economic Value of

America’s Estuaries report.