My path to becoming a coastal scientist

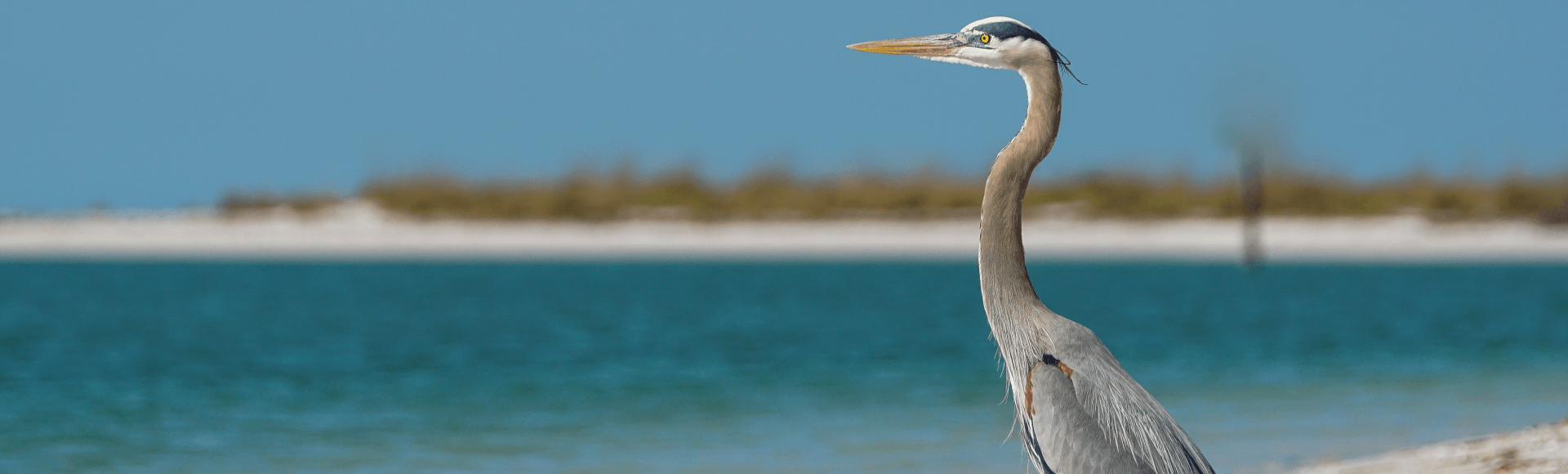

For me, it’s always been about the field work. Feeling the wind in your hair, getting dirt under your nails, and on a really good day, shaking the water out of your ears! These little moments are the reasons why I wanted to study coasts in the first place. I love being outdoors and have always been fascinated by the shoreline – where the land, the air, and the ocean come together as one. The dynamics of a beach, the rich yet harsh coastal habitat, can be a place of serene beauty, but also of awesome power and danger.

After settling in to college, one professor tried to convince me to switch my major from earth and environmental science to chemistry, as I had a knack for inorganics and quite frankly, the department needed more women! He tried to entice me with promises of superior facilities and better faculty ratios. But he couldn’t compete with the field excursions offered in my classes. A bad day in the field beats a good day in the lab, no contest.

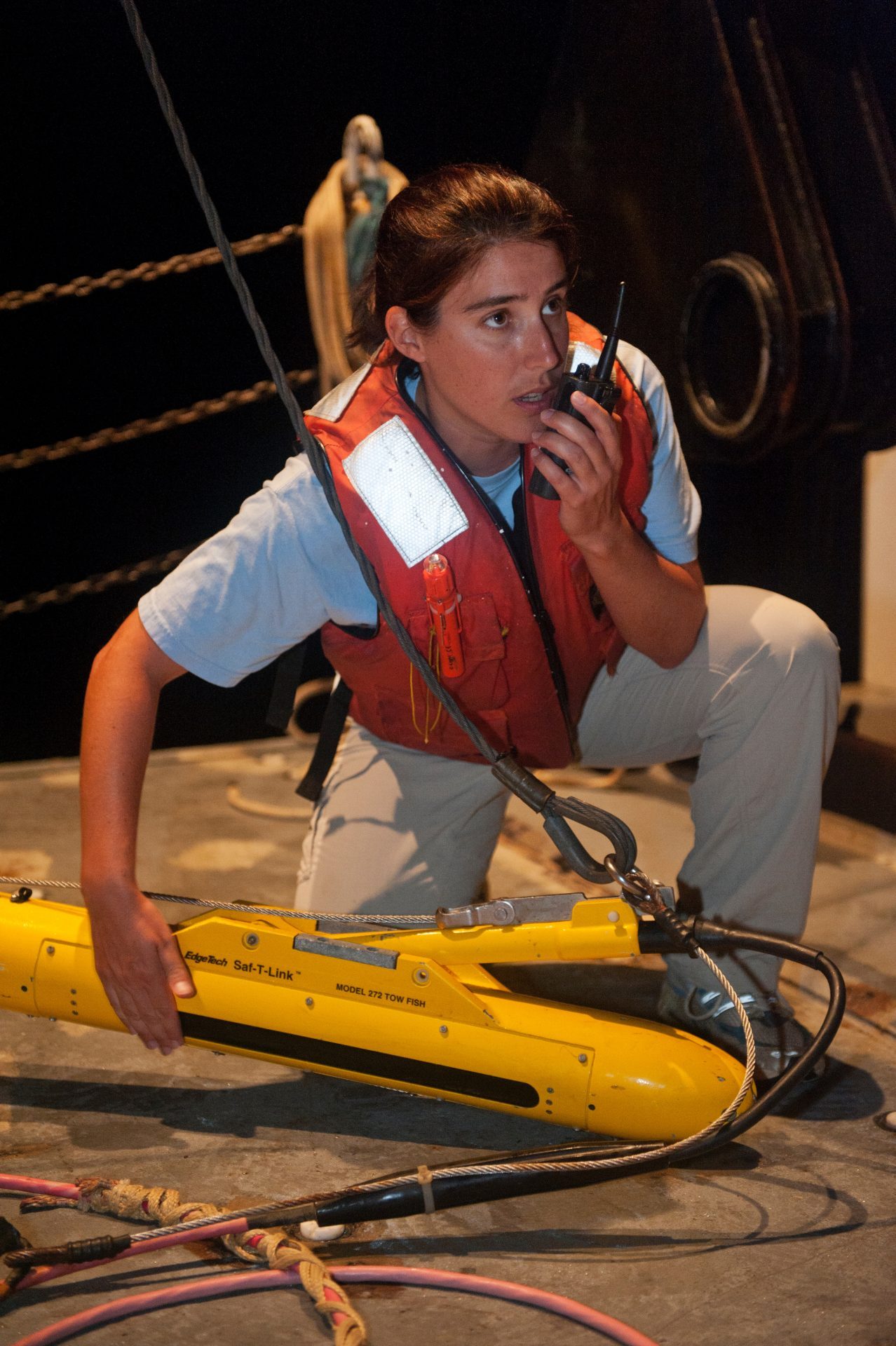

I went on to pursue graduate studies in coastal and watershed systems along the Long Island Sound and later the Delaware Bay. I was part of a graduate student lab group studying marine and coastal geology. Collecting data for our research usually required labor-intensive trips to remote field sites, so we worked together and supported each other when the going got tough. We loaded instruments on large research ships for multi-day trips, and piled onto a skiff for day trips. We worked from the shore, poking around in tidal muck, taking samples of beach sand to analyze. Sometimes, we even lost instruments into the bay and had to don scuba gear to recover it. And on rare occasions, at the end of a long day, we’d go for a cruise to simply enjoy the scenery and remind ourselves how lucky we were to be working in such spectacular places.

As researchers, we sought to understand the physical forces and geologic history that shape our coastal environments. Even then I knew I wanted to spend my career using that knowledge to protect these fragile coastal systems, and to hopefully teach others to love these special places just as much as I do.

Hilary Stevens is the coastal resilience manager at Restore America’s Estuaries.