There and back again: A sturgeon’s tale

This blog is Part 2 showcasing sturgeon restoration in the Great Lakes. Read Part 1 here.

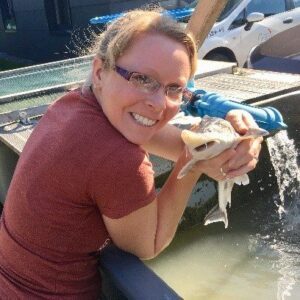

Sturgeon are one of the most fascinating, endearing, and beautiful fish I’ve ever encountered. To say that I’m enamored with them feels like an understatement. For me, it started with a graduate school project on lake sturgeon and has evolved into a deep passion for these fish, complete with an array of home décor my husband lovingly accommodates.

You many not think a fish could be extremely interesting, but consider this: sturgeon have been on Earth for more than 150 million years and coexisted with dinosaurs for much of that time. They are literally living fossils!

In the Great Lakes, my home region, lake sturgeon are the largest and most long-lived fish; they can grow up to seven feet long, weigh nearly 300 pounds, and live more than 100 years! Unlike many fish, sturgeon don’t have scales but instead have five rows of bony plates called scutes that line their torpedo-shaped bodies. Another cool fact, lake sturgeon can extend their mouth downward to pick up food – kind of like having their own vacuum attachment!

The Maumee River estuary, one of the largest rivers leading to the Great Lakes, was once home to thousands of sturgeon that would swim from Lake Erie to the river each spring to lay their eggs. It was estimated that Lake Erie had as many as 1 million sturgeon in the lake, but human actions have reduced that number to such a low level that lake sturgeon are no longer found in the Maumee River.

Now, a team of scientists, led by the U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service, are working to reintroduce lake sturgeon to the Maumee River and restore their once prominent population. Reintroducing lake sturgeon isn’t as simple as gathering some fish from one place and setting them loose somewhere else. There is a lot to consider to ensure a reintroduced population will be successful.

The first step is to make sure habitat in the Maumee is still suitable for lake sturgeon. With sturgeon absent for nearly a century, it’s possible the river could have changed to the point that it is no longer suitable for the fish. My graduate research was focused on determining if habitat in the river could support reintroduced sturgeon populations.

Through this research, I helped measure habitat characteristics like substrate type, water velocity, and water depth, which are important for these fish to reproduce and for baby fish to survive. For example, spawning sturgeon (the reproducing adults) often seek out rocky areas with fast flowing water to lay their eggs. If not enough of this habitat is present in the river, sturgeon will not be able to successfully reproduce. We used this information to create habitat suitability models to find out if the right habitat was in the river. Excitingly, the models identified several large areas within the river that would serve as good habitat for spawning adults and young sturgeon! This means that habitat availability would not hinder reintroduction success.

Another important aspect of planning a reintroduction is that sturgeon imprint, or recognize, the rivers

where they are born and will return to those rivers when it is time to reproduce (similar to salmon). To get sturgeon to come back to the Maumee, we need to raise them in Maumee River water, a process called stream-side rearing.

For stream-side rearing, eggs from a healthy population (one that is large enough to spare some eggs) are collected and then hatched in tanks with water pumped in from the river. Once the baby sturgeon are about five months old, they will be released into the Maumee River. Our team is planning to raise and release 3,000 sturgeon a year for several years to establish a new population.

Before release, each little sturgeon will receive a microchip, similar to one you would put in your dog or cat. The microchips contain an identification number that, when scanned, will tell scientist where the fish came from and when it was released, allowing us to determine the age of some fish and where they might travel.

The Toledo Zoo has developed a stream-side rearing facility on the Maumee River to raise lake sturgeon for reintroduction. 2018 is the first year for stream-side rearing and if all goes as planned, lake sturgeon will be returning to the Maumee River this fall for the first time in a century!

Our team has been working to reintroduce lake sturgeon in the Maumee River for several years, but it will take decades before we fully see the results of our efforts. In addition to their longevity, sturgeon are also very slow to mature and often don’t reach reproductive age until 15-20 years. Because it takes so long for sturgeon to reach maturity and then return to the rivers where they were born (or stream-side reared!), it will likely be the next generation of scientists that carry on our work.

Reintroduction efforts like this one need a sound strategy to closely monitor the population through time, develop public education and outreach for support, establish protections so populations do not disappear again, and create a long-term management plan to ensure lasting success. We have laid the groundwork for the return of lake sturgeon to the Maumee River. Now, we wait with anticipation.

What does it mean to reintroduce an imperiled fish like the lake sturgeon? It means that I get the opportunity to educate and engage with people about this beautiful, charismatic fish. It is a chance to bring attention to the health of our aquatic environments and discuss the importance of biodiversity for our ecosystems. For me, it has been an incredible opportunity to be part of an amazing team of scientists working on behalf of this fascinating species. I can only hope that someday, the results of this work will give my children and grandchildren the experience to develop the same passion for sturgeon that I have.

Plus, sturgeon are awesome!

Jessica Collier is a 2018 Sea Grant Knauss Fellow and the coastal and marine resource specialist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Coastal Program.