For the love of oysters

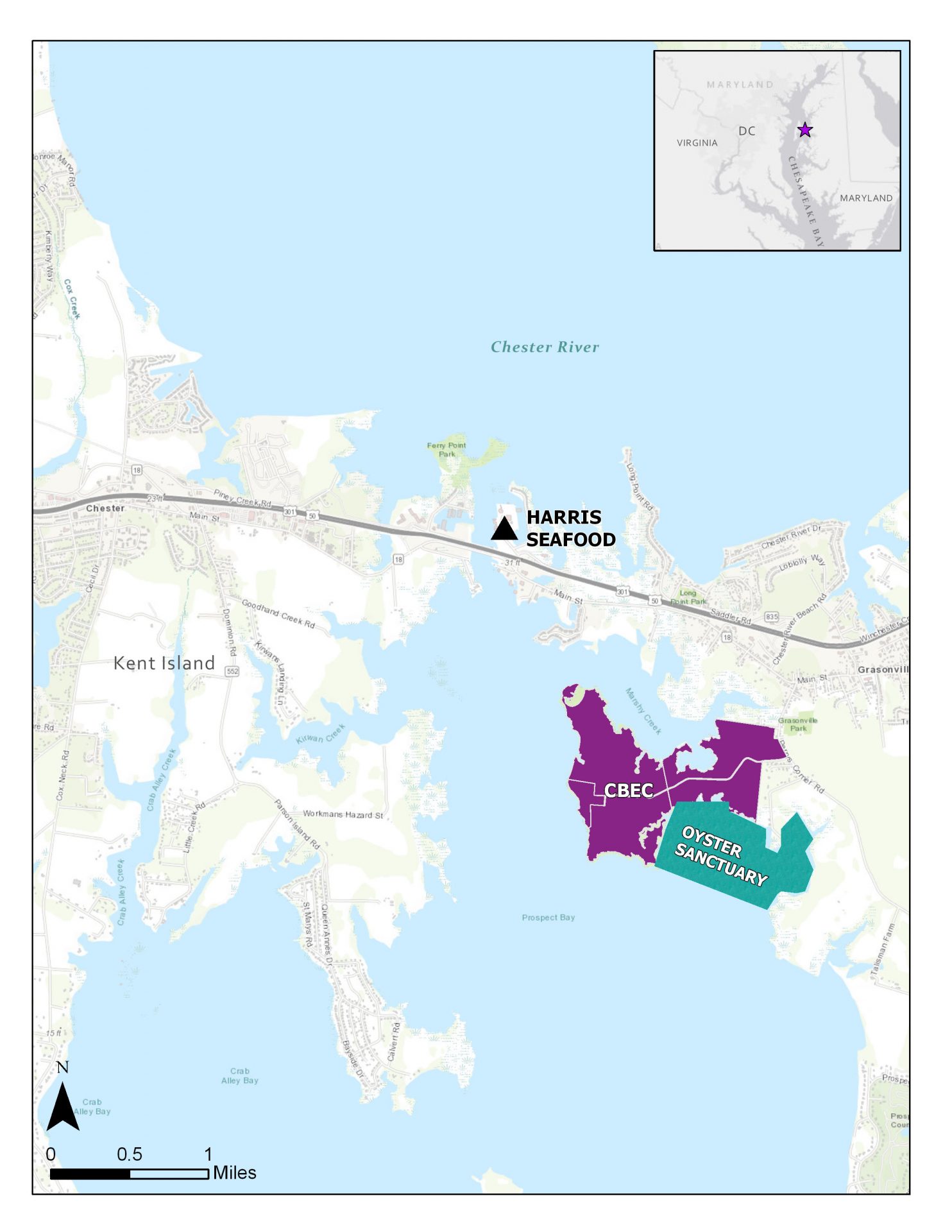

Increasingly, successful habitat conservation requires collaboration among private landowners, businesses, organizations, and agencies. A stellar example of this collaboration is the oyster restoration being done, in Maryland, on the Chesapeake Bay by Harris Seafood, Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center, and the USFWS Coastal Program.

Harris Seafood Company

Although Jason Ruth comes from a family of watermen and seafood purveyors, his parents did not want him to work on the water. Jason recalls his father telling him that making a living from seafood“was a tough life without a lot of consistency.” Despite this warning, he began working at Harris Seafood Company at 13 years old — shoveling and packing oysters. Over time, he assumed other responsibilities, learned the seafood business, and eventually bought Harris Seafood Company in 2004.

As a kid, Jason learned about the historical bounty of the Chesapeake Bay. Captain John Smith’s journals from 1612 described the abundance of oysters laying “as thick as stones” and the diversity of seafood including “sturgeon, mullet, trout, sole, herring, rockfish, eel, lamprey, catfish, shad, perch, crab, shrimp, and mussels.” (Abridged)

He also witnessed firsthand the effects of pollution and over-harvesting on the Chesapeake Bay. In the 1980s, oyster diseases like dermo (Perkinsus marinus) and MSX (Haplosporidium nelson) further decimated the oyster populations.

The decline of oysters and other seafood in the Chesapeake Bay forced the closing of nearly all the packing houses on Kent Island; however, Harris Seafood Company endured. Today, it is the last full-time shucking house in Maryland. Currently, Harris Seafood Company operates year round — employing 57 people, supporting 250 watermen, and generating $25–30 million for the local economy annually.

Conditions in the Chesapeake Bay have gradually improved, due in part to multi-state agreements like the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement and the conservation efforts of numerous agencies, organizations, businesses, and private landowners.

“Today’s watermen (and seafood businesses) have a better understanding of their stewardship role and we are taking action to make things better.”

— Jason Ruth, Owner of Harris Seafood Company

Harris Seafood Company is also contributing to the recovery of the Chesapeake Bay. Partnering with the Queen Anne’s County Watermen’s Association, Jason is working with watermen to establish and maintain several oyster leases, where spat (i.e., oyster larvae) are planted, grown, and later harvested.

The commercial benefits of the leases are obvious — more oysters to harvest and sell. There are other benefits too. Each oyster can filter as much as 50 gallons of water per day. Oyster beds also provide important habitat for fish, crabs, and other aquatic species, as well as foraging for ducks, cormorants, and other waterbirds.

Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center

Another local person trying to improve conditions in the Chesapeake Bay is Vicki Paulas with the Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center (CBEC). The Wildfowl Trust of North America Inc. (Trust) established CBEC with the mission to promote the protection of wetlands for waterfowl in 1998. Due to growing challenges to wetlands and the Chesapeake Bay, the Trust revised its mission to address water quality declines and habitat losses in 2002, with the vision to be a leader in environmental education and restoration.

Vicki Paulas grew up in the mountains of northeastern Pennsylvania — ask her about bears, pierogies, and the Steelers. In 2003, Judy Wink, the executive director of CBEC, lured Vicki Paulas away from her job in Pennsylvania to lead the educational programs at CBEC, and to eventually become the assistant director.

Initially working on maintenance of the 510-acre CBEC property, Vicki eventually was able to focus on habitat restoration projects, such as oyster reefs and a pollinator meadow. CBEC has also implemented restoration projects with communities from Annapolis and Cambridge, Maryland.

Coastal Program

From her first habitat restoration for CBEC — an oyster and reef ball project in 2003 and nearly all the project that followed, Vicki has received help from David Sutherland, Coastal Program biologist. The Coastal Program works with communities to conserve natural places that are important to them by providing technical assistance and financial support.

CBEC was one of the earliest groups to use reef balls to create habitat for juvenile fish and reduce shoreline erosion . The Coastal Program help their efforts by purchasing four reef ball models for CBEC, who plans to create 35 reef balls with the help of volunteers, which will complement other restoration efforts adjacent to CBEC.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for us, has been the easiest to work with!”

— Vicki Paulas, Assistant Director of Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center

Over the years, Vicki and David collaborated on several living shorelines and oyster reefs, including a reef with over 1,000,000 spat planted at CBEC with the help of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Artificial Reef Initiative, and the Coastal Conservation Association. These projects improved fish and wildlife habitat, coastal resiliency, and recreational opportunities on CBEC and in the surrounding communities.

The success of these restoration efforts and CBEC’s unique location garnered attention beyond Kent Narrows. In 2004, Governor Ehrlich designated 287 acres of water around CBEC as an oyster sanctuary and a restoration demonstration area for innovative restoration techniques for the Chesapeake Bay.

Oyster Leases

When Vicki was thinking about new funding source for CBEC, she came up with the wild idea to grow oysters and she approached Jason for advice. Vicki first met Jason, soon after she moved to Kent Narrows, when she asked him for fish and oysters to dissect for one of her education programs. He recognized the importance of CBEC to the community and proposed a partnership to establish and manage the oyster lease among CBEC, Harris Seafood Company, and some local watermen.

“I really don’t like eating oysters, but I am learning how to grow them!”

— Vicki Paulas, Assistant Director of Chesapeake Bay Environmental Center

CBEC’s previous restoration projects with the Coastal Program helped Vicki to create the ideal location for the oyster lease. An oyster lease is an agreement between the State and a person or corporation that wants to raise and harvest oysters in public waters. The lease is protected by living shoreline and reef project implemented with technical and financial assistance from the Coastal Program. The lease also benefited from the previous oyster restoration projects by testing and refining reef building techniques. “These Coastal Program projects improved the chances for success of the lease,” reflects Vicki.

The project began with an oyster lease application, which was granted by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources in 2013. CBEC and Harris Seafood Company purchased 600,000 spat, which were planted by local watermen to create a new reef.

It has been about 3 years since the seeding, and the oysters will be ready for market soon. Profits will be split among CBEC, Harris Seafood Company, and the local watermen. After the harvest, the CBEC and the other partners will seed the oyster lease again.

In the past, watermen and the seafood industry were blamed for the decline of fish and oysters in the Chesapeake Bay. A statistic often cited is that oyster numbers are only at 1 percent of their historical abundance. Everyone agrees that there was overharvesting; however, the decline of the Chesapeake Bay is a more complicated problem and blame should not be placed on any one group. Vicki, Jason, and Dave agree that everyone living in the watershed was and continues to be responsible for the conditions in the Chesapeake Bay.

One final thought from Jason, “Eat less beef. Eat more oysters.” That means you too, Vicki!

Chris Eng is a fish & wildlife biologist with the USFWS Coastal Program.