Habitat helps fish, protects communities, and improves coastal resilience

In a perfect world, every rock pile, undercut, oyster bed, logjam, sandbar and all the other excellent estuary habitat structures we look for would be full of fish. Rods would be bent on every cast and creels would be full at the end of every day on the water.

Anyone who’s been fishing even once knows this just isn’t the case. In fact, quite the opposite is true – which is what makes the fishing more worthwhile in the end, even if some days we curse it for not being so.

One thing most fisherwomen and fishermen have in common, though, is a deep connection to the fish, and the places where we fish.

Typically, these special places have some sort of feature that also make them unique, and we assign them names as such: Pat’s rock, Joe’s hole, Shannon’s ledge. The rock pile or sandbar provide critical habitat for fish, and thus anglers, as well. Even the most forward thinking, sustainable fisheries management policies are helpless if there is not adequate habitat for the fish.

Habitat is not unique to places we actively fish, either. In fact, areas where we don’t fish are equally, if not more, important than the places we do. For instance, migratory fish like salmon and steelhead need open access to their natal spawning grounds to produce healthy offspring. This means navigable waterways that are not impeded by dams, culverts, or other road stream crossings that prohibit upstream navigation.

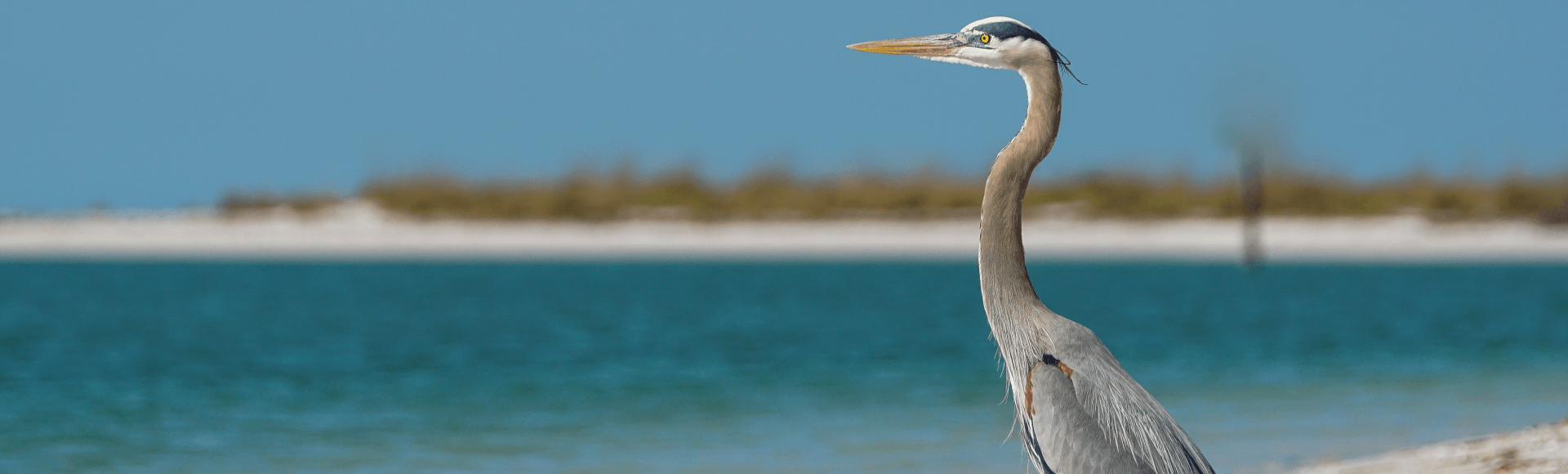

Assuming no obstruction on the spawning migration, juvenile salmon will hatch and eventually grow old enough to feed on their own and they must immediately seek shelter from predators of the aquatic, avian, and eventually humanoid variety. The best place to hide is often in the thick submerged logs and boulders in small, hard to get to, headwater streams. Known as rearing habitat, these areas offer young fish reduced vulnerability to grow safely by feeding on bugs, crustaceans, and smaller fish before heading out to sea to start the process all over again.

Cut out any part of the cycle though, and our favorite fish will begin to disappear before our eyes. Thanks to partners like NOAA, though, we are actively reconstructing this critical habitat for fish, wildlife, and communities.

Putting the pieces back together to recreate natural systems is no easy task, though. Restoration mangers must weigh multiple interests when deciding which projects to take on, and how to best accomplish the intended outcome. The good news, though, is that most habitat restoration projects go far beyond just helping the fish.

The same log jams mentioned above also help prevent erosion during flood events by redirecting rising water levels away from the shore. They also hold back sediment as waters retreat and provide a rich environment for new vegetation to grow, which in turn also aids in erosion control. Preventing erosion along our shorelines protects coastal communities – especially in the face of sea level rise and increased frequency of extreme weather events.

And of course, healthy fish populations contribute to the local, regional, and national economy. Commercial fishing directly employs almost 40,000 Americans. Add in the tourism jobs associated with both commercial and recreational fishing and that number rises into the millions. The downstream jobs associated with packaging, transporting, and sale at restaurants or markets brings that employment numbers even higher.

So next time you’re on the water, and you lose that expensive lure on a submerged log, or a trophy fish breaks your line off on a bed of oysters, be thankful for the time, effort, and money that went to restore or protect this important habitat.

Happy habitat month and tight lines, fellow anglers.

Rob Shane is the Communications Manager for Restore America’s Estuaries. He is an avid fisherman who currently holds fishing licenses in 9 states across the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic. If it swims, he is likely trying to catch it.